One whistleblower gets $30m in the bank, but others count the personal cost

The SEC this week promised an overseas whistleblower $30m – but others who have uncovered wrongdoing haven’t been so lucky

This week, the Securities and Exchange Commission made history by promising an anonymous overseas whistleblower a reward of $30m.

It doesn’t usually work out that way for whistleblowers. Ringing the bell on abuse in a company or government usually means losing jobs and status. The norm is pariah treatment and low-wage jobs, as well as trips to the welfare office and the lingering threat of prosecution or intimidation.

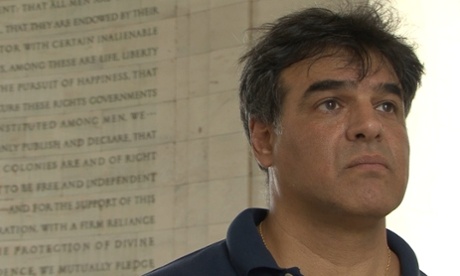

Consider: it’s not every day that you get to buy an iPhone from an ex-NSA officer. Yet a number of people visiting the Washington metro-area Apple store get to do just that. For over a year now, several days a weekThomas Drake puts on his blue Apple work T-shirt and goes to work.

Drake, former senior executive at National Security Agency, is well known in the national security circles. In 2006, he leaked information about the NSA’s Trailblazer project to Baltimore Sun. Years later, in 2010, he was prosecuted under the Espionage Act, but the government ended up dropping all 10 felony charges against him. He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge for unauthorized use of a computer.

Drake, unlike other NSA whistleblowers, has the freedom to move freely within any city or state within America. His freedom, however, comes with a very tangible price: his livelihood.

“You have to mortgage your house, you have to empty your bank account. I went from making well over $150,000 a year to a quarter of that,” Drake says inSilenced, a recently released documentary depicting the lives of several national security whistleblowers. Silenced, which made its debut at the Tribeca Film Festival, is to be screened at additional movie festivals this fall. “The cost alone, financially - never mind the personal cost - is approaching million dollars in terms of lost income, expenses and other costs I incurred.”

“Obviously, I am a persona non grata within the government ... and so I am unemployed,” Drake says to the cameras in Silenced. “I did look for work. I spent a lot of time looking for work. I applied for a part-time position with Apple, and several month later I actually got a phone call. I ended up working at an Apple store in the metro DC area as an expert.”

This kind of result is what most whistleblowers can expect. The potential threat of prosecution, the mounting legal bills and the lack of future job opportunities all contribute to a hesitation among many to rock the boat.

President Obama has approved legislation to help protect federal whistleblowers against retaliation and economic ruin. In November 2012, Obama signed Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act into law, which was to expand whistleblower protections available to corporate whistleblowers to federal workers.

Yet whistleblowers have been left on their own to struggle with the consequences of going public.

Jesselyn Radack says whistleblowers need better protections. She is a former Justice Department ethics attorney and whistleblower who went on to defend Drake and Kiriakou. She is currently one of Edward Snowden’s lawyers.

“The Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act ... has a big loophole that covers national security and intelligence officials, people exactly like Tom Drake at the NSA, Edward Snowden at NSA, and John Kiriakou at CIA, Steven Kim at the State Department, Jeffrey Sterling at the CIA, Peter van Buren, who was at the State Department – the people that I would argue we most need to hear from and want to hear from,” says Radack, noting that Obama’s order applies only to employees – not to contractors such as Edward Snowden.

Finance whistleblowers can, theoretically, collectawards ranging from $300,000 to $104m for disclosing secrets about their employers cheating on taxes and violating securities law. Activist investor Bill Ackman offered a $250,000-per-year-for-10-years deal to an employee of Herbalife for supporting Ackman’s thesis that the company fools its workers and customers. The company and other hedge fund managers, including Carl Icahn, dispute Ackman’s remarks.

The price of leaking national security problems, in particular, is steep. National security whistleblowers have no prospect of financial rewards.

Kiriakou, a former CIA analyst, became the first former government official to confirm the use of waterboarding against al-Qaida suspects in 2009. Three years later, in 2012, he was prosecuted for leaking classified information under the Espionage Act. After he was accused of violating the Espionage Act, Kiriakou had to look for employment outside the field of national security.

“I have applied for every job I can think of – everything from grocery stores to Toys R Us to Starbucks. You name it, I’ve applied there. Haven’t gotten even an email or a call back,” Kiriakou says at some point in the film. “I’ll be honest with you, I really miss working and so regardless of what the job is, I’ll be happy to just pass eight hours a day.”

He was not the only one in his family to lose his job as a result of his disclosures. His wife quit her job because of threats of security investigations, says Kiriakou.

After both of them were unemployed for seven months, she informed him that they couldn’t afford food for the next week. In the days to follow, they found themselves at a welfare office, where they were told they qualified for a variety of assistance including food stamps, medicaid and job training.

The stark reality of their financial situation was enough to get Kiriakou to consider changing his plea. That, and the possibility of not seeing his children grow up.

“She doesn’t make enough money to support our household. We could borrow enough for two years to keep her going,” he says. “But if I am found guilty and get more than two years, I mean - we think we are ruined now? - we’d be ruined permanently after that. I want to fight it but I have kids and I just can’t risk them losing me for six to twelve years.”

Kiriakou is currently serving a 30-month jail sentence. Instead of telling his children that he is going to jail, Kiriakou and his wife have told them that he is going to Pennsylvania to “teach bad guys how to get their diplomas.”

With Kiriakou in jail, his family continues to struggle to make ends meet.

“They are still in dire straits, living from pay check to pay check,” Radack told the audience at the New America after recently held screening of Silenced. A Facebook page, Defend John Kiriakou, lists instructions on how to contribute to Kiriakou’s commissary account. Another post invites supporters to buy him a subscription to The New York Times’ Sunday edition. Radack already purchased him a Monday through Saturday subscription. He receives all papers two days after they are published.

“I am sitting in front of you as a free human being, I can’t tell you what it means to be free,” Drake told the audience after the screening. “I paid an incredibly high price.”

No comments:

Post a Comment